From mom-and-pop shops and venerable independents to new outposts of proven chains, in the last year restaurants have been dropping like flies.

But while it might seem that closure after closure is an indication that the entire industry is about to implode, that is not the case, according to The NPD Group, which found that some savvy operators are still growing rapidly despite what is now being called The Great Recession.

According to NPD’s spring 2009 ReCount census of restaurant locations, more than 4,000 restaurants have closed their doors in the past year. Yet while that number may seem large, it’s only about a 1-percent decline, NPD found.

“This is not a pretty picture,” said NPD analyst Bonnie Riggs. “[But] we have to remind ourselves…this is a huge industry. We make 65 billion visits to restaurants in a year. We are still making visits to restaurants. It will come back.”

Of the 578,000 restaurants in the United States, 54 percent are independents, 29 percent represent major chains and 17 percent are small chains.

In aggregate, independent operators suffered the most unit closures. There are 5,207 fewer independents serving consumers today than just one year ago, the Port Washington, N.Y.-based market research firm found. At the same time, consumers have 1,165 more major chain units from which to choose.

“More than half of all units are independents, and that’s who’s getting hit the hardest,” Riggs said. “It’s harder to do business as an indie.”

Whether independent or chain, full-service operators, with their higher check averages, are feeling the heat more than limited-service operators. According to the data, 3,768 of the total units closed occurred in the full-service sector, while just 255 were in quick service.

“The reasons are clear,” Riggs said. “Consumers must pay more for their meals at full-service places than at QSRs; full-service business mix is weighted to supper, where demand is weakest; and the sector felt the effects of slowed demand earlier in 2008 than their quick-service counterparts.”

While closures occurred in every area of the country, some regions have lost more than others.

New York, home to Wall Street, where the economic collapse began, has seen the greatest number of independent closures. The Big Apple lost 430 independents between the springs of 2008 and 2009. Among the city’s most recent—and much talked about—losses is Café des Artistes, the opulent, old-world eatery whose owners closed for vacation in August and then decided not to reopen.

Miami/Ft. Lauderdale, where the housing crisis has been particularly acute, saw the closure of 244 independent units, NPD found. During the same period, Dallas/Ft. Worth, Cleveland and Indianapolis each lost upwards of 150 independent restaurants.

Independently owned restaurants felt the pain most sharply, but many chains were hurt as well. According to NPD’s ReCount data, in the year ended spring 2009, the fastest-declining chain was Quiznos, which closed 414 units. There also are nearly 200 fewer Bennigan’s because of the 2008 bankruptcy of the casual-dining chain’s parent company.

Several frozen-treat concepts had major meltdowns, including, TCBY, which closed 189 units; Dairy Queen, which closed 135 units; and Cold Stone Creamery, which closed 120 units, NPD found. Other fast-declining chains included Domino’s Pizza, Blimpie and T.J. Cinnamons, all of which closed more than 100 units.

It’s not unusual to see this downward trend in unit closings during a recession, Riggs noted. For example, during the recession of 1990-1991 unit closures continued for two years until demand levels recovered and began to grow. Operators culled under-performing units, placing more emphasis on improving same-store sales performance, she added.

“This is a kind of righting itself,” Riggs said. “It does happen each time…there’s a shakeout.”

Yet amid all the turmoil, some operators are finding ways not just to survive, but thrive, rapidly opening units as competitors crumble beside them.

Among the fastest-growing chains is Milford, Conn.-based Subway, which opened more than 600 U.S. units in 2008. The sandwich chain attributes some of its ability to expand in a recession to the popularity of its $5 Footlong promotion, but also credits its ongoing practice of streamlined operations, smaller prototypes and the concept’s overall value message.

“It’s not just about the $5 Footlong—it’s keeping the proper economics on your restaurant,” said Don Fertman, Subway’s director of franchise development. “We’ve been able to weather the storm because we recognized from the outset how to watch costs while providing a good value.”

According to NPD, other fast-growing chains include Pizza Hut, which added more than 900 units of its Wingstreet concept; Dunkin’ Donuts, which opened 590 units; and Little Caesars, which opened nearly 300 units.

Consumers’ desire for the comfort of a good hamburger at an affordable price is among the many reasons Five Guys Burgers and Fries stores have been popping up around the country despite the worst economic crisis in decades, chain officials said. The Arlington, Va.-based chain opened 132 units in 2008 and more than 120 so far this year.

“I think it has a lot to do with burgers as a product,” said Greg deCelle, Five Guys’ chief development officer. “It’s a comfort food. It’s a good quality product at a good value.”

| Wingstreet | 913 | Quiznos Subs | -414 |

| Subway | 645 | Bennigans | -192 |

| Dunkin’ Donuts | 590 | TCBY | -189 |

| Little Caesars | 299 | Domino’s Pizza | -151 |

| Five Guys | 157 | Dairy Queen | -135 |

| Jimmy John’s | 157 | Blimpie | -131 |

| Panda Express | 110 | Cold Stone | -120 |

| Tim Horton’s | 104 | T.J. Cinnamon’s | -112 |

Some chains believe they are able to expand while others are closing because they offer not only good food at a value, but also unique dining experiences. For example, Tempe, Ariz.-based Tilted Kilt Pub & Eatery, a Hooters-like sports pub, opened 14 units in 2008 and is on track to open at least 30 more by the end of the year.

“Tilted Kilt brings the dining experience to a whole new level through entertainment and fun, which drives sales even in a bad economy,” said Mark Hanby, Tilted Kilt’s vice president of franchise development. “Landlords don’t want another ‘me too’ concept. They recognize that to be successful they need to offer consumers a different type of experience to enjoy, and we provide just that.”

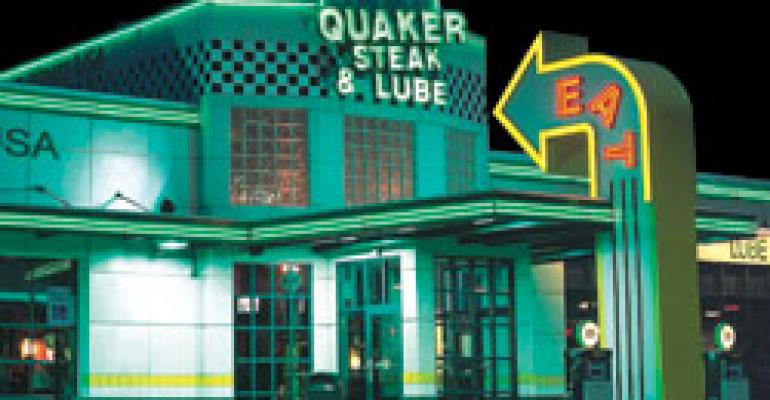

Similarly, while many casual-dining chains are closing units, Sharon, Pa.-based Quaker Steak & Lube recently opened its 37th location. The motor-sports-theme concept best known for its wings attributes its continued expansion to the many events and promotions it offers.

“You can go anywhere and have a meal, but you can go to the Lube and have a meal and attend a great event,” said Jamie Cecil, the Lube’s director of franchise sales and development.

Among the crowd-drawing events at the Lube are Bike Nights and Car Cruises, parking lot parties complete with DJs, vendors, contests and food for motorcycle or classic-car enthusiasts.

For other operators, opening more locations is the cause, not the result, of success.

New York-based Union Square Hospitality Group recently announced plans to open soon the fourth unit of its popular Shake Shack, a burgeoning gourmet-burger and milk shake chain. The company also earlier this year launched several restaurants and concession stands inside Citi Field, the new home of the New York Mets baseball team. Before the year is out, the multiconcept foodservice company, which also operates fine-dining restaurants such as Eleven Madison Park, Gramercy Tavern and Tabla, plans to open Maialino, a full-service Italian concept in the Gramercy Park Hotel.

“We in our company have always felt like during the most windy storm we grow our roots deeper,” said USHG managing partner Randy Garutti. “We do that by continuing to grow. We just bear down even more…more attention to detail.”