Amounting number of layoffs at restaurant companies nationwide has industry insiders worrying about a huge long-term loss of talent as foodservice tries to weather short-term economic troubles.

In recent weeks at least seven large restaurant companies have announced layoffs that have put thousands of people in the ranks of the unemployed. But in the race to rein in corporate overhead, companies are causing an exodus of veteran talent from an industry that long has lamented its difficulties in finding and keeping workers.

“I’ve never seen anything with these kinds of cuts ever happen before,” said 20-year foodservice veteran Orrick Nepomuceno, who is now a human resources consultant for restaurant operators.

Since December, several prominent casual-dining, quick-service and fast-casual chains have cut positions. Among them, Starbucks Coffee Co. slashed 200 workers and 380 unfilled slots; Lone Star Steak-house, 1,500; Brinker International, 125 corporate jobs; Buca Inc., 13 percent of its staff, including its chief executive; Domino’s Pizza, 55 positions; Rock Bottom Brewery Restaurants, 19 percent of its staff; and Einstein Noah Restaurant Group, 18 jobs, including those of 15 district managers.

“It seems the hospitality industry is moving into turtle mode and pulling its head back in to wait and see what is going to happen to the economy,” said Masha Schricker, who lost her job as human resources director after 13 years at Einstein Noah, the Lakewood, Colo.-based bakery-cafe franchisor whose system includes more than 600 Einstein Bros. Bagels, New York Noah’s Bagels and Manhattan Bagel outlets.

Einstein Noah and other companies cited rising commodity and energy costs and shrinking consumer spending among their reasons for cutting jobs.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics counted 88 layoff actions in January in the category of accommodations and foodservice, which includes hotels and restaurants. Those actions accounted for more than 6,000 unemployment claims. That compares with 56 layoff actions and more than 4,000 claims in January 2007.

At the same time, however, the bureau noted that the industry continues to add jobs—albeit at a slower pace. The federal agency recently reported that from November to February the foodservice sector added, on average, 12,000 jobs per month, compared with an average monthly gain of 28,000 jobs for the 12-month period ending in October.

“Even though the industry is having shifts, there are still pockets of growth,” said Alice Elliot, founder of Tarrytown, N.Y.-based executive search firm The Elliot Group.

Job demand appears to be the strongest in the front- and back-of-the-house. Most of the recent layoffs affected middle-level managers and corporate employees—experienced workers who may end up leaving the industry, observers said.

Chris Donner in Dallas was one of 125 employees cut from the payroll at Brinker International Inc., the parent of more than 1,800 restaurants, including such concepts as Chili’s Grill & Bar, Romano’s Macaroni Grill, On the Border Mexican Grill & Cantina and Maggiano’s Little Italy. The majority of those laid off held corporate positions at Brinker. Donner had spent the past two years in Brinker’s new-restaurant development division. Most of his co-workers there lost their jobs as well. Before the layoffs, Donner had applied for a position in Brinker’s global division. After the cuts, he was hired back as a senior manager in the global division. But by early March, he was one of only two people among his terminated colleagues that had found work.

Donner started an Internet message board where he and his former co-workers could exchange job leads and encourage one another in their job searches. They were real estate managers, developers and architects at Brinker who are finding it difficult to search for similar jobs in the industry, Donner said.

“You can’t do a job search for a restaurant site developer,” he said. “You get things like real estate jobs or construction manager. That’s not what we do.”

The biggest long-term risk for the industry from the recent layoffs is losing experienced veterans to other industries, observed Nepomuceno, who owns a practice in conjunction with Dick Wray Executive Search in Raleigh, N.C.

“The midlevel, pre-executive positions are really the ones in danger,” Nepomuceno said. “Restaurants are taking away their core guts. You will see a lot of people migrating away from the restaurant industry.”

Schricker, formerly of Einstein Noah, has since interviewed with some technology companies, but no restaurants, despite her desire to stay in the industry and find a company with the same positive environment she experienced at Einstein Noah, she said.

“In both IT interviews, people said, ‘We love the fact that you understand high turnover, we love that you understand customer service and you bring experience that people from other industries don’t bring,’” Schricker said.

Smaller and regional companies will be the most likely to snap up experienced industry executives who have lost their jobs, recruiters said.

“It becomes a good time for [recruiters] because not everyone is laying off,” said Don FitzGerald, vice president of operations for Wolfgang Puck Worldwide in Beverly Hills, Calif., a co-founder of the Association of Hospitality Recruiting Executives and a former executive recruiter for the Elliot Group. “There are still some companies that are doing great and very good people, who through no fault of their own, have to make a change.”

When larger corporations cut back, it bodes well for smaller emerging companies, noted Eric Goodwin, founder of Goodwin & Associates Hospitality Services LLC, in Concord, N.H. The HR and management placement firm has 20 offices along the East Coast.

“Overall, our clients are aggressively hiring managers and looking to grow,” Goodwin said, “and they run the full gamut in the hospitality industry—casual theme, fine dining, corporate level as well as franchise groups.”

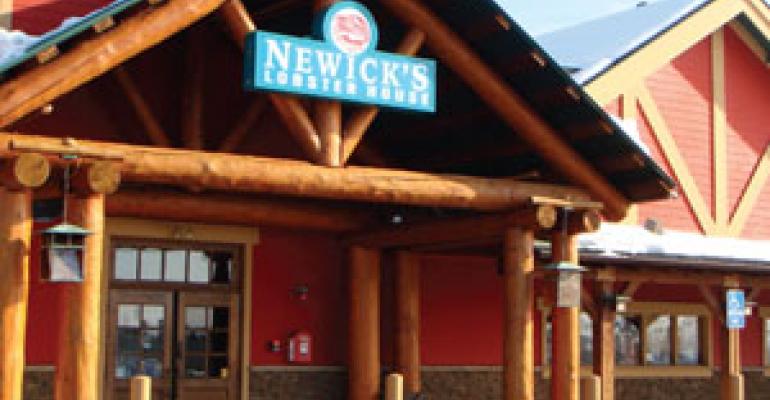

One of the firm’s clients, Dover, N.H.-based Newick’s Hospitality Group, a 60-year-old family-run company, recently hired its first manager from outside. Last spring, Newick closed two of its aging and oversized Newick’s Lobster House units in Portland, Maine, and Merrimack, N.H. In November, the company opened a smaller, modernized unit in Concord, taking over a shuttered Smokey Bones restaurant. More than 200 people showed up for a job fair for the new restaurant, said chief executive Steve Newick.

“Our goal is [to] open one restaurant per year for the next five years,” he said. “There is a lot of doom and gloom, but someone has to make the economy go. It might as well be us.”