High real estate costs have conspired with record-high prices for gas and commodities to slow expansion for many restaurant companies, but operators are finding development bargains by converting defunct restaurant spaces into their own concepts.

And a flattening-out of costs that had soared in recent years for construction and some building materials, combined with a return to competitive bidding among contractors hit by slumps in the housing market, also are providing rare values for operators that are able to expand in the troubled economy.

Chains and independents that don’t require exact footprints for all of their new units are economizing on startup costs by remodeling buildings previously opened by companies that have been forced to close underperforming units.

Some operators are finding that those buildings are in better locations than they would find if they built on undeveloped land.

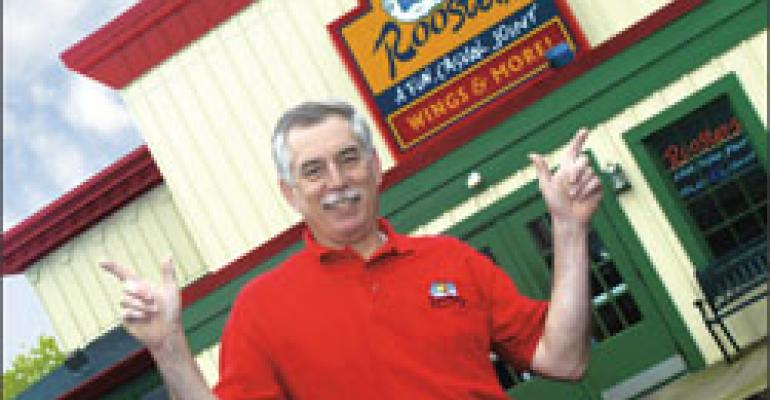

“A lot of concepts aren’t making it, and that gives us a lot more inventory to choose from,” said Shannon Foust, president of 18-unit Roosters, a casual barand-grill chain based in Dublin, Ohio, that he invested in after leaving his leadership post at the Damon’s Grill chain last year. All of Roosters’ new units are conversions of other restaurant concepts.

As more such buildings become available, their price drops, Foust said, noting that properties once costing $1.2 million now often sell for $800,000. One Roosters unit was leased for $500,000 and required $600,000 in remodeling. With average-unit sales of about $2 million a year, startup costs can be recovered quickly, he noted.

Some of the properties converted to Roosters units previously were leased by Ryan’s Family Steak House, Ponderosa Steakhouse, Bob Evans and some independents. Foust found that the locations were excellent, in spite of his initial fears that a dependence on existing locations could be a barrier to entry for franchisees.

Panera Bread franchisee John Walch of Carlon Corp. in Brookfield, Wis., recently leased a freestanding building in Ashwaubenon, Wis., near Green Bay, that formerly housed a Krispy Kreme Doughnuts branch. Although Panera usually builds from the ground up, Walch got permission from the franchisor to lease the site, which he called a “phenomenal” location.

“It made a lot of sense to us,” said Walch, who operates 22 Panera units.

He is not yet sure, though, if his construction costs will make his total startup expenses lower than building from scratch, since the building will be gutted.

“It’s easier to find subcontractors now,” he said, “but the labor savings may be eaten up by material costs that have gone up.”

Material and lumber costs have fallen in some markets, such as California, said speakers at the recent UCLA Extension California Restaurant Industry Conference in Los Angeles. Some chain restaurant executives who attended said construction costs that had risen anywhere from 7 percent to 10 percent annually for the past several years now have flattened out, and building contractors are actively bidding against each other for the first time in recent years.

Not all markets are offering real estate bargains, however. Landlords in Chicago and its desirable suburbs, for instance, have not reduced prices, even on former restaurant properties that have been vacant awhile, some real estate brokers said.

There currently are no good deals in downtown Chicago in areas where businesses want to be, said Doug Simons of Simons Restaurant Exchange, based there. Operators willing to locate in suburbs that were overbuilt may be able to find discounts, he said.

“We have a number of those deals where landlords won’t budge, even though they are losing money on a daily basis,” said Mel Melaniphy of Site Relocation Specialists, another Chicago firm. “They are still thinking it’s two years ago. Landlords aren’t desperate enough yet.”

Meanwhile, potential restaurant tenants continue to scout around the country for properties they can convert easily and are looking at well-located sites that used to house such concepts as Romano’s Macaroni Grill, Lone Star Steakhouse & Saloon, Hops Grill Brewery, Bakers Square and many others that have downsized.

“We are busier now than in the last few years,” said Richard Lackey, a broker in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., and chairman of the Council of International Restaurant Brokers. “In my 35 years’ experience, there are more restaurants closing and in trouble today than ever before. Yet, restaurants are still opening, and landlords are willing to work with them.

“The big restaurant companies are saying they will not roll out as many, but they are looking for bargains. They realize it’s cyclical and the market will come back up.”

One conversion Lackey’s firm brokered was at a leased site that had been an Irish pub in Palm Beach Gardens but now is a branch of the white-tablecloth Bice chain of Italian restaurants. New York-based Bice bought the lease-hold for a fraction of the original investment, Lackey said.

In addition to saving money on startup costs, buyers of existing leaseholds usually can save time in getting their concepts open, often within as little as six months after signing the lease, said Paul Fetscher, president of Great American Brokerage in Long Beach, N.Y. Opening a built-from-scratch restaurant typically takes about 18 months because of increasingly arduous local-government approval processes, he said.

Although many built-out restaurants can be converted effectively to other concepts, some cannot, Fetscher said, citing older IHOP A-frames as an example. He also said chain franchisees who aren’t committed to opening in the nation’s top markets, where costs remain high, would find much better real estate deals.