“This is a disrespectful approach.”

Those are the words of Adir Michaeli, the owner of New York City’s Michaeli Bakery who is suing Grubhub, Uber Eats and DoorDash for charging above the mandated 20% delivery fee cap set by the New York City Council in 2020. Michaeli cites in the suit that he was routinely charged 25% or more even after the fee caps were put in place.

“I had to know legally if they were really doing what I thought they were doing, which is illegal,” he said. “If so, this is really, really bad ethically.”

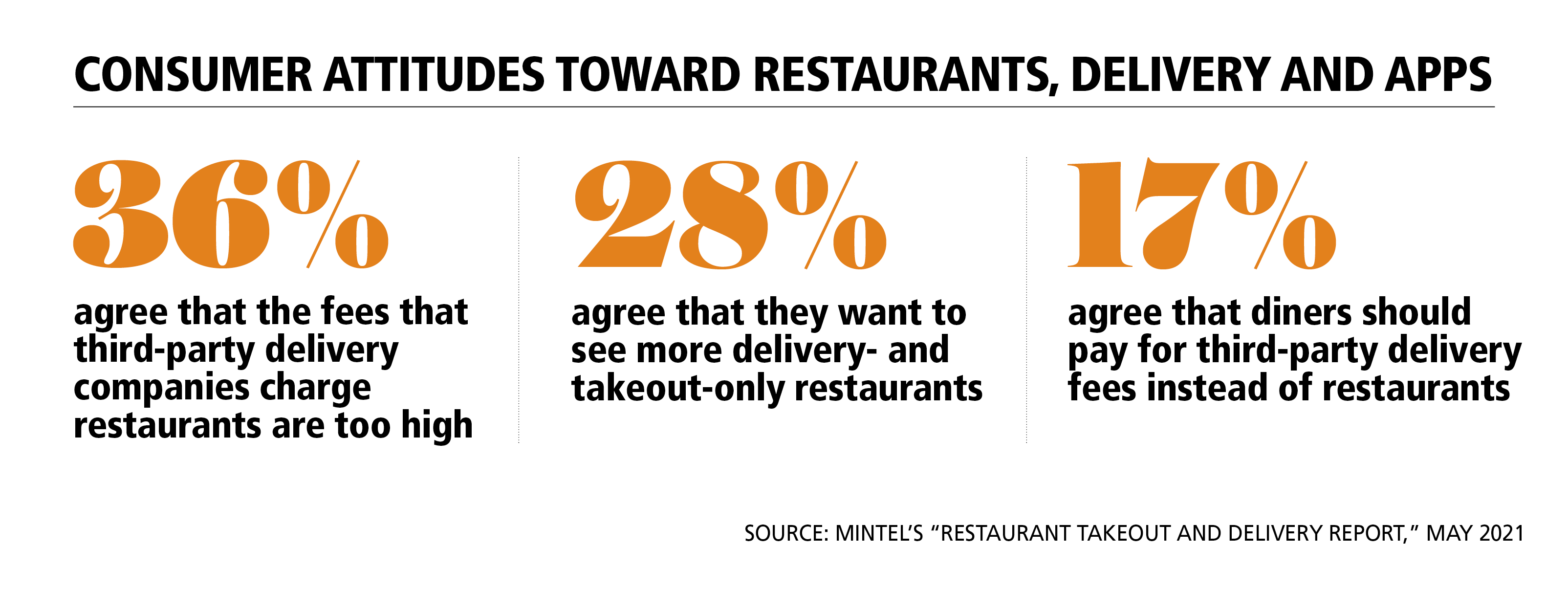

Michaeli’s situation illustrates the tenuous relationship between restaurant operators and third-party delivery services. While these platforms have been a lifeline for countless restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic, many independent operators in particular have struggled to make them financially feasible. And though local regulations in some of the nation’s biggest cities have tried to cap delivery fees at 15% or 20%, Grubhub, Uber Eats and DoorDash have been accused of routinely charging additional fees over the limit.

Michaeli, who said he can’t afford an in-house delivery driver, said he thinks 20% is the fair market value for the services provided by third-party delivery companies.

While the delivery environment is different for chains than it is for independents, some chains are trying to break their dependence on the third-party delivery players. Take Portillo’s, for example. The 65-unit chain switched to an in-house and third-party delivery hybrid during the pandemic.

Early on, CEO Michael Osanloo approached Portillo’s senior leadership team about taking delivery partially in-house.

“Our CEO Michael Osanloo challenged us and said, ‘You know, I'm watching all these third-party drivers come in and I'm wondering why I can’t give those orders to my own team members,’” said Nick Scarpino, senior vice president of marketing and off-premises dining at Portillo’s.

The Chicago-based chain was in a unique position for fast-casual operations in that the brand wasn’t suffering in the beginning of 2020 financially; in fact, it was doing well because of its stores with multiple drive-thru lanes.

The Chicago-based chain was in a unique position for fast-casual operations in that the brand wasn’t suffering in the beginning of 2020 financially; in fact, it was doing well because of its stores with multiple drive-thru lanes.

Within a matter of days, Portillo’s was able to bring some delivery in-house, creating a new position for existing team members, which helped retain staff. Portillo’s used the platform CartWheel to help move its services in-house (it later invested in one of the company’s seed rounds because Portillo’s leaders were so happy with the transition).

Despite the success, the fast-casual brand isn’t taking every delivery order. Orders under a certain dollar amount (varying store to store) are still directed to DoorDash since they’re not financially worth it for the restaurant to make the delivery.

Portillo’s hired, certified, trained and equipped 300 drivers across its system, with 75% of the new drivers being existing team members who were cross-trained.

“We didn't force anyone to become a delivery driver; everybody who signed up raised their hand, so clearly there was some pent-up demand within our own team members to do deliveries,” Scarpino said.

Besides leveraging it to invest in Portillo’s team members, the in-house delivery program lets Portillo’s control the experience from beginning to end, he added. That creates value for the guest and supports team members with tip money.

Other chains have opted to take delivery completely in-house and have leveraged new platforms that have sprung up to support restaurants in their efforts to detach from third-party services. The 50-unit casual chain Bareburger is one; it uses Lunchbox, a technology developed by its former CMO Nabeel Alamgir after he discovered how much the chain was paying Grubhub.

Other chains have opted to take delivery completely in-house and have leveraged new platforms that have sprung up to support restaurants in their efforts to detach from third-party services. The 50-unit casual chain Bareburger is one; it uses Lunchbox, a technology developed by its former CMO Nabeel Alamgir after he discovered how much the chain was paying Grubhub.

“I saw that one year we cut [Grubhub] a $6 million check for fees, and that's the equivalent of opening six Bareburgers or the equivalent of employing 600 people,” he said.

In response, he founded Lunchbox, a technology platform with a goal of helping provide many of the services that the major delivery providers do, such as marketing, technology integration, consumer data, POS, website design and more. But Lunchbox doesn’t provide drivers — clearly a crucial part of the delivery process.

Other services have sprung up offering driver help, including delivery co-ops like Loco Co-op, which is in six cities across the country. In that model, the co-op lets restaurants work together, owning shares of the service in a particular city and splitting profit.

Initial fees are 15% but are expected to be lowered. Any excess fee revenue is distributed back to investors.

Other companies have opened with a narrower focus. Black and Mobile, which is in four cities across the country, is a service by and for Black restaurant owners in heavily African-American localities. Citing the lack of access to capital for people of color, Black and Mobile charges less and organizes in its communities by hiring local people and increasing employment rates so local consumers have more to spend, as well.

Contact Holly Petre at [email protected]