In this in-depth investigation, NRN looks at how restaurants can recover from a culture of substance abuse.

Thirty-five years ago, when Mickey Bakst walked into his first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, he realized he was the only hospitality worker in the group.

“It was all doctors, lawyers and housewives,” he said.

The general manager of the famed Charleston Grill credits AA for keeping him alive over four decades. But to survive in an industry where illicit drug use is rampant, he and fellow recovering addict and Charleston, S.C., restaurateur Steve Palmer had always talked about creating their own restaurant support group.

But the idea faded until 2016, when one of Palmer’s chefs, Ben Murray, committed suicide.

Murray, who worked at Town Hall in Florence, S.C., was a graduate of The Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, N.Y. He ended his life after a long battle with addiction. Bakst and Palmer, managing partner at The Indigo Road Hospitality Group in Charleston, were hit hard by Murray’s death.

“There’s no longer an excuse. We have to do something,” Palmer said.

Ben’s Friends was born soon after. The fledgling support group held its first meeting at Indigo’s Cedar Room, in Charleston’s historic turn-of-the-century Cigar Factory.

The group’s mission is simple: provide a safe haven for restaurant workers looking to get or stay sober.

Unlike AA, there is no set agenda at Ben’s Friends. Attendees simply riff on whatever is on their mind — namely the unrelenting pressures of hospitality work.

More than two dozen servers and chefs showed up to the first meeting. Their stories were similar.

Bakst said many talked about nearly “losing their shit” while dealing with an uptight chef or serving an obnoxious guest. The instant camaraderie was palpable.

“In any kind of therapeutic venture, there is comfort in familiarity. In AA, you share the common bond of being completely powerless to your alcohol and drugs,” Bakst said. “If you add the fact that you have a similar work situation, it creates a tighter bond that people hold on to.”

The weekly Sunday and Thursday meetings in Charleston are typically run by Palmer or Bakst. In less than two years, other chapters have sprouted in the Southeast.

The weekly Sunday and Thursday meetings in Charleston are typically run by Palmer or Bakst. In less than two years, other chapters have sprouted in the Southeast.

North Carolina chef Scott Crawford is going on 14 years of sobriety and founded the Raleigh chapter of Ben’s Friends. Atlanta also has a chapter, and others are coming soon to Charlotte, N.C.; Nashville; and Richmond, Va.

“It’s just taken a life of its own,” Palmer said.

Palmer, sober for 16 years, said he was especially heartened to see the importance of Ben’s Friends during the annual Charleston Wine and Food festival this year. Many out-of-town hospitality workers came to a meeting looking to escape temptation, he said.

Attendance has grown to represent a wide swath of foodservice workers: caterers, alcohol distributors, fast-food owners, managers and even a celebrity chef or two.

As word spreads about the group, unsolicited donations have poured in. The non-profit uses the funds to place restaurant workers in sober living homes.

Palmer considers this goal vital for recovery because workers tend to room with other foodservice workers — many of whom are not the best role models.

“I hate to be villainous of the industry, but there’s unique social circumstances that exist in our world,” Palmer said.

And the harsh reality is that support groups and programs can’t save everyone.

Ben’s Friends can attest to that. Bakst said many attendees come and go. One worker placed in sober living recently fled — and she was never seen again.

It’s disheartening. But then Bakst thinks about the day when an ex-server walked into the Charleston Grill after being gone a year. He handed Bakst his one-year sobriety coin.

Restaurateurs Mickey Bakst, left, and Steven Palmer, are the co-founders of Ben’s Friends, based in Charleston, S.C.

The young man, who attended an early Ben’s Friends meeting, said Bakst gave him the courage to get sober. And that “makes it all worthwhile,” he said.

Helping hospitality beyond fine dining

Ben’s Friends and private Facebook forums like Chefs with Issues are among a few organized support groups aimed at helping restaurant workers struggling with depression, addiction and other disorders.

But those groups are primarily geared for workers at upscale venues.

What are large quick-service chains doing to help employees struggling with addiction?

Many chains declined to comment when asked by Nation’s Restaurant News. However, Denver-based fast-casual chain Noodles & Company, known for its employees-first mantra, was willing to speak about the subject.

“Our first core value is we care about our team members. It doesn’t matter to us if they’re with us a year or six days,” said Sue Petersen, vice president of human resources.

Peterson and Amy Cohen, director of benefits and compensation, outlined employee wellness perks that range from supporting paddle-boarding to providing personal time off for those seeking addiction help.

The latter is an extension of the FMLA (Family and Medical Leave Act), a federal law that requires employers to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid job protected leave for workers who need to address a serious health issue or care for a family member.

Attending rehab is a qualifying event, but Cohen said Noodles & Company takes it one step further.

FMLA only applies to employees who’ve logged 1,250 hours or been on the job for a year. So Noodles & Company has its own personal leave policy for employees who have worked at the company less than a year. They can take up to 12 weeks of unpaid time off for any qualified reason. That could range from taking a sabbatical or caring for a family member dealing with addiction.

“It’s been part of the Noodles culture to provide these lifestyle benefits,” Cohen said.

The company also offers financial assistance through its Noodles & Company Foundation. It can be tapped by any employee in times of crisis. That could include paying for rehab expenses or wages from lost time away from work.

The company also takes a preventive approach to wellness with Balance Bucks, a perk for corporate employees, general managers and multi-unit managers.

The program allows eligible Noodles & Company employees to be reimbursed up to $650 for engaging in activities that promote a balanced lifestyle. Qualifying programs include gym membership fees and yoga.

But, it also foots the bill for unconventional items such as hiking gear, paddleboards, ski equipment — even birthing classes.

“Whatever the employee defines as their personal wellness is how they can utilize that benefit,” Cohen said. “For some, it’s the gym or hiking. It’s what is meaningful to them.”

A focus on young workers

Large multi-unit foodservice and hospitality brands remain aware substance abuse is a problem among its workers, but they also persist in being tight-lipped about how to deal with the workforce problems.

“If you take the occupation and the age group and combine them, young restaurant workers — the 18- to 25-year-olds — are at the highest risk for not only substance abuse but other mental health issues,” said Joel Bennett, president of the Fort Worth, Texas-based Organizational Wellness & Learning Systems.

While many of the sobriety programs are employee-based or created outside the corporate structure, companies can be supportive of those efforts and also provide resources and training, Bennett said.

Bennett and his group have worked with groups including the National Restaurant Association and restaurant companies like Dallas-based casual-dining chain TGI Fridays. The latter, like a number of other large restaurant companies, declined to expand on the breadth of its programs.

Bennett and his group have worked with groups including the National Restaurant Association and restaurant companies like Dallas-based casual-dining chain TGI Fridays. The latter, like a number of other large restaurant companies, declined to expand on the breadth of its programs.

“It has been a long-term battle because so many people — one third of the population — got their first job in a restaurant,” he said, adding that in public health the young restaurant workers are a vector, or a point where the science shows significant relations to the problem.

“If you are going to try to prevent substance abuse problems in the population at large, you should target young restaurant workers,” he said.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s benchmark “Report on Alcohol, Drugs and Health” in 2016 cited OWLS among just a few programs that met criteria for workplace alcohol and drug abuse prevention.

Paving the way for addiction treatment

Gary Mendell, chairman of Norwalk, Conn.-based HEI Hotels & Resorts, has a personal connection to his efforts to help young people with substance-abuse struggles: He lost his son to drug addiction in October 2011.

Mendell started a group called Shatterproof to help others. New York-based Shatterproof works with and advocates for families with members facing addiction issues and recovery.

“For every major disease in this country, there is one well-funded national organization — but not for addiction,” he said.

“For every disease, there’s an organization devoted to funding the discovery and implementation protocols and programs related to prevention, treatment and recovery, changing public policies and supporting families as they navigate some of the most trying times that they will ever face. For every major disease, but not for addiction.”

Late last year, Mendell convinced four of the five major U.S. insurers — Aetna, UnitedHealth, Cigna and several Blue Cross plans — and a dozen smaller companies to sign onto Shatterproof’s eight principles of care for patients struggling with addiction.

Mendell said he hoped the insurance companies, which cover about 250 million patients in total, could help make it easier to access addiction treatment and medications that help those with opioid addictions.

“One thing that we found is the 18- to 25-year-old restaurant employee — or even those 16 to 30 — are going through significant developmental changes,” he said, and may not be as interested in wellness.

Companies can foster team resilience with what Bennett called the five Cs. The first three are Confidence, Commitment and Centering, and the corporation can help with the last two: Community and Compassion.

“Young workers like to talk to each other,” he said. “You can do exercises with them to get them to talk to each other. … Managers who create an atmosphere where there is an openness to talk to each other and allow them to rely on each other can help them get through difficulties.”

Restaurants often don’t have the funding to do a workforce program, and the industry, especially in restaurants that serve alcohol, offer an availability to addictive products.

“By creating a team environment where workers adhere to the five Cs, it not only helps with substance abuse but the other counterproductive behaviors like sexual harassment,” Bennett said.

Read more:

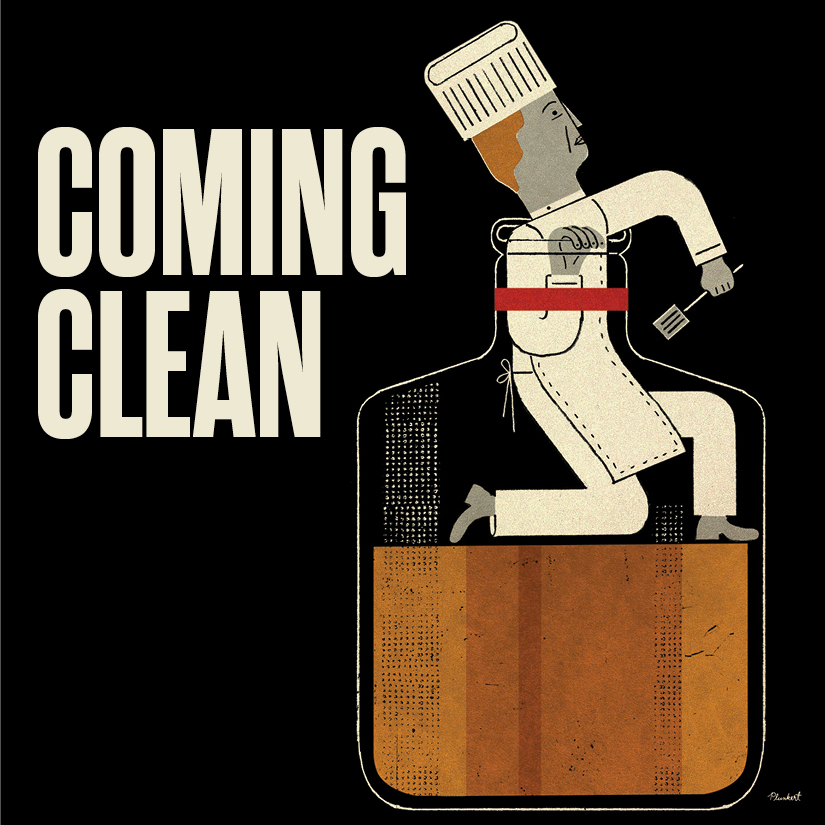

Coming Clean: Recovering from a culture of substance abuse

Is the notorious world of restaurant partying taking a sober turn?

Why the opioid crisis is a restaurant crisis

7 practices to avert substance abuse in restaurants

Ron Eyester on sobriety: 'I've honestly never felt worse'

Staying sober while running a whiskey bar

Do you have to leave foodservice to stay sober?

Column: A restaurant employee, an opioid addict, my son

7 things to know about the opioid crisis

Contact Nancy Luna at [email protected]

Follow her on Twitter: @FastFoodMaven