Shochu hasn’t yet followed tequila and cachaça into the mainstream of American spirits, but proponents say it’s just a matter of time until the eminently mixable Japanese liquor makes the jump from ethnic obscurity to bar staple. It has a lot going for it—boutique image, versatility, relatively low alcohol content, purported health benefits and even snob appeal, with some brands fetching triple-digit price tags. It also seems poised to flow along with the growing interest in authentic Asian foods and beverages.

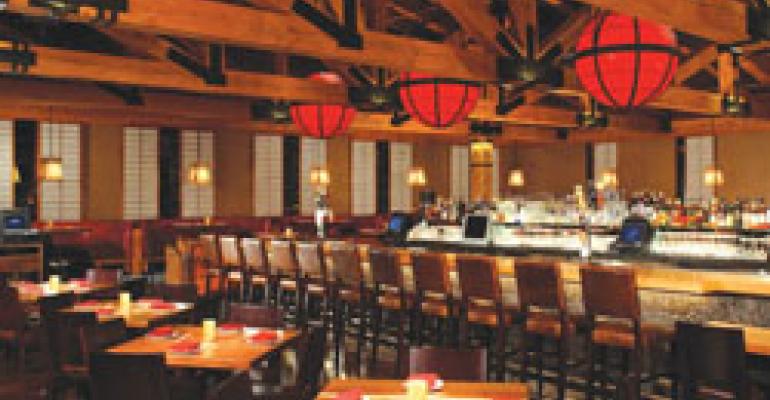

It already is popular in some Asian restaurants, like Taneko Japanese Tavern in Scottsdale, Ariz., an izakaya, or Japanese-style pub, created by P.F. Chang’s China Bistro Inc., the Scottsdale, Ariz.-based casual-dining chain.

“Our shochu cocktails are the most popular of our specialty drinks,” said operating partner Mark Evensvold, who has four shochu cocktails on his drink list and occasional shochu specials.

The spirit has captured the imagination of restaurateurs Lynn Wallack and John Handler, owners of Deleece, an American restaurant that debuted in Chicago in 1995. The couple is opening a restaurant-lounge this spring called Shochu, also in Chicago. The spot will showcase 20 brands of its namesake spirit and a variety of specialty cocktails, along with small plates of Asian-edged food.

“Shochu mixes like vodka, gin and tequila,” said Wallack, who ticked off shochu mojitos, shochu Bloody Marys and shochu mimosas as a few of the cocktail ideas. “It also goes well with purées, muddled fruits and just a splash of simple syrup or soda. It mixes great with just about anything.”

It is made from a variety of starches, including barley, wheat, rice, sweet potato and sugar cane, fermented and distilled into a clear spirit that Westerners liken to vodka. There are big differences, however. Shochu is less potent—usually around 25 percent alcohol, compared with 40 percent for vodka—and it retains more of the flavor of the raw materials than ultra-refined vodkas.

Japan’s shochu craze encourages proponents. Since 2004, shochu has outsold saké there.

“More and more people there are drinking shochu instead of saké,” said Monica Samuels, saké ambassador for Southern Wine & Spirits in New York and former corporate saké sommelier for Sushi Samba, a Japanese-Brazilian-Peruvian restaurant chain based there. “It lends itself better to the nightlife scene.”

But only in recent years, Samuels said, have the Japanese considered shochu respectable, let alone trendy, thanks to the rise of boutique-grade shochus. Traditionally, it has been the drink of the poor. Can it cross over to non-Asian restaurants?

“In contrast to saké, which a lot of people consider a drink to pair with food, this is a drink to have as a cocktail or after-dinner drink, so it really can go with any cuisine,” Samuels said.

At Taneko, shochu stars in creations like the berry-laced Shibuya-tini for $9 and the Ropponngi Fizz for $8, made with shochu, lychee, yuzu and fresh citrus. The bar stocks three types of shochu: Nakanaka Nai, which is made from rice and aged in cedar casks; Honkaku, made from wheat; and Ginza No Suzume, from barley. The latter is the choice for cocktails—“it seems to mix better,” Evensvold said. The rice and wheat shochus are what Japanese guests typically drink on the rocks. Lately, Taneko has succeeded with a new wrinkle—infusing shochu with fresh papaya and strawberries to create a unique fruity libation.

“People are loving it,” Evensvold said.

Wallack and her partners essentially stumbled upon shochu.

“The more we learned about it, the more interested we became,” she said.

What swayed them, in addition to its taste and mixablity, she said, were its reported health benefits, chiefly an abundance of an enzyme said to dissolve blood clots and prevent heart attacks and strokes.

“We wanted to be innovative, so we said, ‘Let’s open a place featuring this,’” Wallack said. “We’ll also have a full bar and good beer and wine lists, but this gives us a point of difference and another reason to try us.”

One initial challenge they faced was sourcing the product. “It was work just finding distributors and importers to get it from,” Wallack said.

Wallack has heard from local retailers that some consumers are becoming curious about shochu and asking for it.

“There seems to be a buzz starting,” she said. “We want to be in on the ground floor of this.”