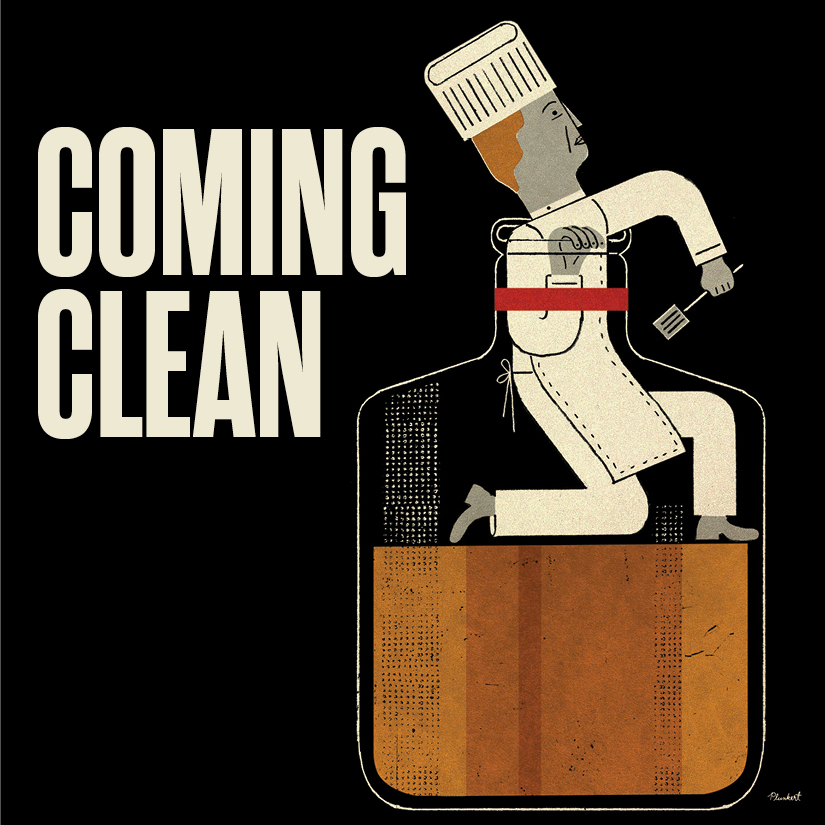

In this in-depth investigation, NRN looks at how restaurants can recover from a culture of substance abuse.

As at most high-end restaurants, the staff at Canlis in Seattle end the dinner shift late, but they’re often looking for a way to spend some time winding down before they head home. In many restaurants, that means gathering at the bar to raise a glass or two — or more. But at Canlis it might mean pulling out some laser tag guns or Ping-Pong tables instead, just to play a bit and blow off steam. “It’s about creating community and setting some standards, and just giving people something else to do, other than sitting at the bar with a drink,” said Katie Coffman, director of operations at Canlis.

It doesn’t happen every night, Coffman added. But it’s one example of the way some in the industry are hoping to change the culture within restaurants that has been blamed for the high rates of alcohol and illicit substance use.

Restaurants are notorious as workplaces where intoxication, both during and after hours, can become a way of life.

There are free or discounted “shift drinks” offered to employees as a perk, and customers who leave drugs as a tip. There are the stories of dishwashers with a cache of illicit substances, or line cooks who fill their water bottles with vodka to keep a steady buzz through dinner service.

“Chefs in general, and servers, and GMs — everyone — is surrounded by alcohol all the time,” said Alex Levin, executive pastry chef of the Boston-based Schlow Restaurant Group, which operates concepts like Cavatina in Los Angeles, Doretta Tavern in Boston, and Casolare Ristorante in Washington, D.C.

“Go out to a restaurant at 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock at night in any city, and people have just been through a very busy, high-tense — even if it’s not tense it’s been a highly focused four- or five-hour situation and the need to unwind is a powerful driver,” Levin said.

Some in the industry work 50- to 70-hour weeks pouring everything they have into their jobs, he said.

Those people may be looking for a way to decompress from their intense work life, he said, “and the quickest way to do that is by having a few glasses of wine or going out to a bar with some friends and partying a little.”

A backdrop of intoxication

“One restaurant manager joked recently that the restaurant industry is entirely made up of functional alcoholics,” said Kevin Finch, executive director of Big Table, a nonprofit with offices in Seattle and Spokane, Wash., that offers crisis support, coaching and mentoring to the working poor in the restaurant industry. “But I would argue some are functional and some are not so functional.”

With more lawsuits coming to light in the wake of the #metoo movement, the picture painted of inappropriate behavior in restaurants often comes with a backdrop of intoxication.

In the sexual harassment lawsuit filed earlier this year by a former manager of Mike Isabella Concepts, for example, Chloe Caras said the group’s partner, Mike Isabella, routinely drank throughout the day at his restaurants and that his behavior while intoxicated was often belligerent, threatening and sexually inappropriate. She believed she was fired by Isabella during a “drunken tirade,” although Isabella said in a statement that her allegations were untrue.

The New York Times account of allegations of sexual harassment at The Spotted Pig in New York City includes stories in which owner Ken Friedman invited an employee to his car to smoke marijuana, and rowdy drinking sessions after shifts. Friedman was described as often intoxicated at work, and they said he pressured staff to drink and takes drugs with him and guests.

The Washington Post in December portrayed chef Mario Batali as a “hedonistic master of excess” who, when drinking, was prone to sexual misconduct and abusive behavior. In a statement to the Post, Batali apologized for being “a drunken and idiotic fool.”

“The link between drugs and alcohol and all of these abuses, whether sexual or otherwise, is directly related,” said Erik Oberholtzer, co-founder and CEO of the chain Tender Greens, based in Los Angeles, who previously spent years as a chef in the fine-dining world. “We shouldn’t be drinking in the workplace. But you’re basically throwing a party every night.”

Add to that the fact that restaurants attract all sorts of people facing all manner of pressures in their own lives, he said.

It is physically, emotionally and mentally demanding. Wages are low. It involves late hours and getting off work at a time when mostly only bars are open. Workers tend to be young and inexperienced.

“It’s a chicken and egg thing. Are people drawn to restaurants because they know it can be a big party, or does the restaurant create the [culture of] partying?” said Shaaren Pine, founder and executive director of Restaurant Recovery, a support network for restaurant workers struggling with addiction, seeking sobriety or in recovery.

Shaaren Pine, founder and executive director of Restaurant Recovery

Changing tradition

But people like Pine see the restaurant industry at a turning point.

It might be because of greater access to healthcare, or greater awareness of the opioid issue, she said. Or it could be simply the fact that people are getting tired of going to funerals for their friends and coworkers.

“If you ask anyone who works in a restaurant, ‘Do you know anyone who has died [as a result of substance abuse],’ invariably they’ll say yes,” Pine said. “But equally devastating is when someone can no longer be a parent or be part of a family, or be functional in the life they maybe wish they had or had before.”

First launched in 2012, Restaurant Recovery took a hiatus but is relaunching this spring with services in Washington, D.C., Boston, New York and Miami.

“It’s a sober support network,” Pine said. “You don’t have to keep suffering. There is another way. We don’t have to be dying. We don’t have to keep going to funerals. We don’t have to not talk about it.

“And also, we don’t have to glamorize it,” she added.

Fundamentally, the restaurant industry fuels the party, Pine said. It’s built into the way restaurants operate.

“The industry is very permissive,” she said. “Everything seems normal because people are doing the same or worse than you are. In a regular industry, you’d probably be fired if you missed work, or you were drunk at work or some other something had happened. But in the restaurant industry, you could probably keep your job in the same place, or you could find another job within the industry very quickly.”

Pine said she was in the industry for 12 years, most recently as a manager at the now-defunct restaurant The Argonaut in D.C.

After dealing with addiction in her own family, Pine said she tried to change the culture of drinking at the restaurant.

No longer were workers given two free shift drinks, for example. The restaurant instituted a drug-free workplace policy. She told people when hired that a drug test would be requested in the event of a crime or accident. There would be no more drinking on the job, and if workers came to work under the influence, they would be sent home.

“At the time, that was pretty radical,” she said. “We thought people wouldn’t want to work for us if we took away their free alcohol. And that’s an industry problem. But, in the end, it strengthened our team at the restaurant.”

Two-time James Beard Award nominee and three-time semifinalist chef Katie Button also made the decision to enact a zero-tolerance policy at her Heirloom Hospitality Group restaurants in Asheville, N.C.

Button, who trained as a pastry chef at the world-renowned El Bulli in Spain, makes it clear that drinking on breaks or after work is forbidden on premises. Integrity is important. “I pride myself on professionalism,” she said.

The Cornell graduate launched the program at her first restaurant, Curate, in 2011. She did it, in part, because she wanted to establish a new mindset for an industry known for its “bad boy, bad girl” culture.

“I really want to focus on the people doing good in the restaurant industry,” she said.

Setting a good example is so crucial to her ethos that Button said she won’t accept an invite from employees to go drinking after work at another restaurant.

“That might make me seem less approachable or not their best buddy because I’m not going out to the bar with them,” she said.

Button’s program is not meant to be punitive. Instead, it’s about creating a safe and healthy environment for workers. To reinforce that, Heirloom Hospitality debuted a program that offers free counseling for workers dealing with any serious problem, such as drug addiction or financial insecurity.

Katie Button of Heirloom Hospitality Group has a zero-tolerance policy at her restaurants.

Sobriety is the new black

Ron Eyester, executive chef and general manager of the restaurant Food 101 in Atlanta, said, “Sobriety is like the new black in the restaurant industry. There are so many sober people, it’s crazy.”

And that fact eases the path for those seeking recovery who want to stay in the industry, he said. “I can look back on some other older people that I’ve worked with over the years [and they would say], ‘Yeah, that guy’s sober,’ and it would baffle me,” he said. “I was like, how can that guy be sober and still be in this industry. And now here I am; I’m one of them.”

Oberholtzer of Tender Greens said his company is part of a generational shift that hopes to bring an end to some of the industry’s more notorious stereotypes. The fast-casual chain doesn’t have a bar, but it does serve beer and wine.

“With Tender Greens, it’s always been a reaction to the world we came from. There was sexual abuse, physical, psychological and wage-and-hour abuse. And there was substance abuse,” he said. “For myself and my partners, we always thought when we had the opportunity to build something, we’d do it differently.”

That meant building a company that offered workers a more balanced life, with more reasonable work hours and a culture that exemplified the use of the word “tender” in its name.

“It’s all about care, creating an environment, both internally and externally, that’s heartfelt,” he said. “What that does is create an environment where people feel a bit more whole, a bit more cared for, and therefore don’t have to self-medicate.”

The company has even paid for employees going to rehab. “It goes beyond the ‘just say no’ side of things,” Oberholtzer said.

For a growing company, a key factor is having a human resources professional or department on board, he added.

“As much as HR can be the brakes on the fun machine, you don’t want the chef to be the HR department,” he said.

“When you introduce an HR professional, they’re going to remind you that there is risk. The more you professionalize that component in the business, the safer you are as a company. But more importantly, it becomes a better workplace.”

Bret Thorn and Nancy Luna contributed to this report.

Read more:

Coming Clean: Recovering from a culture of substance abuse

Why the opioid crisis is a restaurant crisis

Beyond AA: Where restaurant workers go for help

7 practices to avert substance abuse in restaurants

Ron Eyester on sobriety: 'I've honestly never felt worse'

Staying sober while running a whiskey bar

Do you have to leave foodservice to stay sober?

Column: A restaurant employee, an opioid addict, my son

7 things to know about the opioid crisis

Contact Lisa Jennings at [email protected]

Follow her on Twitter: @livetodineout